As I mentioned before, I’m in the middle of a busy, busy period of travel and talking — not as busy as many of you are all the time, but much busier than I usually am. I just finished up one of the events I was most looking forward to – a week of talking to FYE faculty and librarians at the University of San Francisco. It was a whirlwind — 3 undergraduate classes, 2 workshops and a 90 minute talk and I am definitely still processing.

In the middle of all of the preparations for this curiosity/inquiry/FYE extravaganza — some thoughts clicked together in my head and re-framed a thing. And this is a thing I’ve been talking about, struggling with, soapboxing about for a long time — the peer-reviewed sources requirement for first-year students. Long-time readers will know that I’ve been going on about this for years now — here’s the TL:DR version:

to find, identify, read, evaluate and use peer-reviewed sources effectively requires an epistemological framework most first-year students do not yet have and which cannot be “taught” by simply requiring the source type. And because it’s not taught any other way, many students leave us not knowing how to use research or science to help them solve problems, make decisions, or understand the world.

I’ve been talking about this a long time, to librarians and to faculty. And my thinking has changed and evolved, and the conversations have been good and gotten better. But I still come out of them feeling like I failed at same level. The more I think about these topics, the more radically I think how these concepts are taught needs to change, and I regularly come away feeling like I failed to really convince faculty to radically rethink how they approach peer review, or I feel like I failed to give any truly helpful ideas for doing so.

But as I said, some things came together and helped me reframe my approach and I honestly think it made a difference. I feel like this was the best and most fruitful “how do we teach peer review” conversation I’ve ever had. Now, part of this might be that the USF faculty and librarians are awesome, but since I frequently get to talk to awesome people, I’m thinking the reframing might have had a bit to do with it. So I thought I’d share in case this frame is useful to others.

As always, here’s the context …

Thread #1:

My daughter came with me on this trip — she loves San Francisco & the USF campus and knows some of the people I work with here — and because my schedule was so jam-packed, she went off and sat in on some things that interested her more. One was a course on the rhetorics of gender and sexuality taught by the excellent Sarah Burgess. Sarah sent the readings in advance just in case Anna wanted to prepare; as it turned out, this was going to be the Judith Butler week.

My daughter came with me on this trip — she loves San Francisco & the USF campus and knows some of the people I work with here — and because my schedule was so jam-packed, she went off and sat in on some things that interested her more. One was a course on the rhetorics of gender and sexuality taught by the excellent Sarah Burgess. Sarah sent the readings in advance just in case Anna wanted to prepare; as it turned out, this was going to be the Judith Butler week.

(Don’t worry – there’s no Butler quiz at the end of this story. Gender Trouble is important in this story for context only)

Now, we didn’t want Anna to go in totally blind here because Butler is challenging, but time got away from us & we left a day early because of a last-minute emergency itinerary change (and the dog ate our homework and our grandmother is sick and we had to drive our roommate to the emergency room) so we didn’t do the reading. So my last night at home I was listening to my husband giving Anna a Butler primer while we ate a quick pre-airport-shuttle dinner.

Shaun is a cultural geographer and has worked long and hard for about a decade on the Intro to Cultural Geography survey. One of the things he’s struggled with (and largely conquered) is helping his students to understand and define culture in a new way. Most students come in thinking of culture as something we use to describe groups or to distinguish groups from each other (Italians eat pasta; Dutch people ride bicycles) — it’s an understanding of culture that’s baked into books like this:

Now, obviously What is Culture? is a course (or book, or series of books) in itself, but to hit some highlights of the many, many, conversations we’ve had about this at our house — this is a view of culture that obviously simplifies a complex picture. Just trying to think of examples to clarify “describe groups or distinguish groups from each other” — how many examples that come immediately to mind do you also dismiss immediately as the worst kind of stereotype?

Now, obviously What is Culture? is a course (or book, or series of books) in itself, but to hit some highlights of the many, many, conversations we’ve had about this at our house — this is a view of culture that obviously simplifies a complex picture. Just trying to think of examples to clarify “describe groups or distinguish groups from each other” — how many examples that come immediately to mind do you also dismiss immediately as the worst kind of stereotype?

So one of the things that Shaun does at the start of the class is introduce a definition that better accommodates the diversity of cultures we all navigate every day — the diversity that exists within groups and within times and places — culture is what people do. And honestly, it’s amazing how many times this phrase now comes up in daily life at our house. Obviously, culture is what people do was going to be the starting point Shaun and Anna used to start discussing Butler.

Thread #2

Increasingly, I’ve been mentally modeling what I do as cultural — my students are entering a new cultural space and infolit instruction in the first year is so much about helping them to navigate this space, or making the constructions, assumptions and values of this new cultural space (the academy, or higher ed) visible. That’s why I get uncomfortable when people argue that we should be entirely focused on the after-college infolit picture. Yes, I think that it’s important that students go out with the skills, dispositions and understandings I want them to have, but I also think that’s important that they understand how to navigate the culture they’re going to be spending the next 4-6 years immersed in successfully.

And more importantly, I think that framing it in this way — as a type of cultural literacy — helps them learn how to integrate what they need from this culture as they navigate others. While they may not need to access original studies every day after college (most people don’t) they still need to understand how research and theory is used to understand the world, solve problems, and justify decisions if they are going to critically understand the world around them. Problems come up when we treat the cultural assumptions of academia as absolute, static values, but being literate in that culture is useful.

But for some reason, I never combined this thought with culture is what people do until I was on the plane to San Francisco.

The result.

I already had a substantial piece planned on the “3 peer-reviewed articles” requirement so it didn’t take more than tweaking to reframe the conversation in terms of culture, but it made a big difference.

Starting with culture is what people do —

This definition comes from Understanding Cultural Geography by Jon Anderson, and I find it really useful thinking about libraries and infolit. Especially the top part — the material things, social ideas, performative practices and emotional responses about research, information and knowledge creation — that pretty much captures what I do, right?

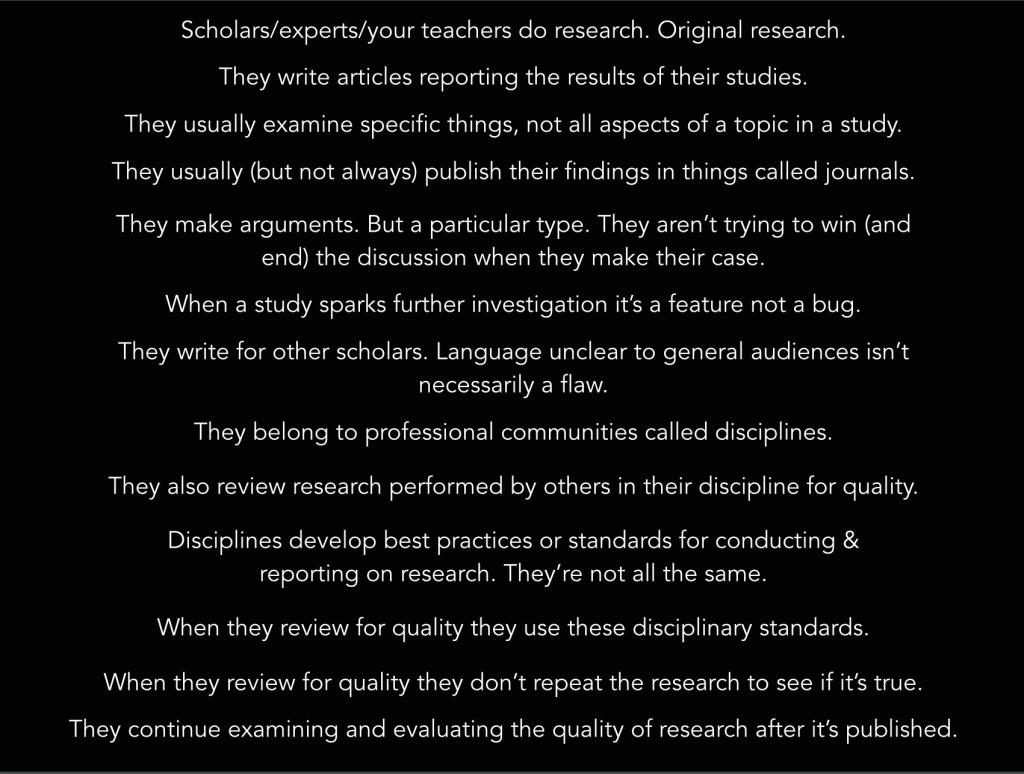

And I had already generated a list of things that I thought students needed to know to understand peer review — I went through and reframed this around what people do:

So going back to the 3 peer reviewed articles requirement. I asked the faculty and librarians in this audience to brainstorm around this question:

What do first-year students need to know about what people do in this cultural space (the academy) in order to effectively find, read, evaluate, understand and use these sources?

And it took a minute, but the group ran with it. They said students would need to know that people do research, they report it in journals, they review other research, they use a shared understanding of how knowledge is created to do these things, and so on. And after 10 minutes or so of discussion, they’d at least touched on almost everything on my list.

I still went through every item on this list because I really do feel like all of these things are necessary if students are really going to find peer-reviewed sources (and know what to expect in them when they do find them) read and understand what they’re trying to communicate, use them meaningfully, and evaluate them against the standards they were trying to meet.

And there were pieces that the faculty didn’t come up with exactly — I think the struggles students have with what peer reviewed studies are good for might be more visible to librarians who get the “I want a peer reviewed article that describes the pros and cons of school uniforms” questions all the time. I also spent some time on the pieces in the middle, about how students need to understand that a piece of scholarship or theory that pushes an academic conversation to a new place is important and valuable even if subsequent research or theorizing shows some limitations or flaws in the original piece.

These are all issues I have talked about before with faculty and with librarians and I have had some great, inspiring conversation with both of those audiences. This one felt different though and different better, and I think the shared framework of what people do was really important to that.

Off the top of my head, here’s what I liked about it —

It let us talk about what students don’t know in a way that didn’t frame everything as student deficits or gaps.

I’ve tried a lot of different ways to demonstrate “no, really, you have to actually teach this.” A lot of these are drawn from my experience — things I’ve noticed and reflected upon and used to shape my own pedagogy. But in many cases, I’ve really struggled with the “should I use this” question because a lot of these come from the questions students have, or the misunderstandings those questions reveal.

For example, I had a student who thought that breast cancer was “too narrow” to do her FYC argument paper on. When I realized that she thought that not because she didn’t understand the scope of the literature, but because she thought that science was about facts, not argument — that was really, really important to me. It helped me start to see how many of these gaps were not about information literacy, but about epistemology. And that example can be powerful when I share it too. But the first impulse most audiences have when they hear that “breast cancer = too narrow” equation is to laugh. And I’m not sure that any subsequent explanation that I do after that can really shift us away from a focus on students as deficient.

With this frame we were entirely focused on what we do, not what they do, and I liked that better.

This frame let us talk about what faculty do as something that is important and valuable, but not universal.

I think in past conversations there’s been a subtle “what students really need to know isn’t what you do” message that would bug me too if I were someone engaged in research I was excited about. But, at the same time, it is true that lots of students we teach aren’t going to be in a position where they need to access the primary research on a daily basis (nor will they have the same tools to do so). So this balanced across that well – I was able to frame it in a way that says students need to understand academic culture not just to succeed as students (though that’s important) and they need to learn about research not just to become critically informed citizens (though that’s important). I’ve tried to frame it in that way before, lots of times, but this time it felt more like that message was heard.

The frame itself suggests things we can do.

As I said, I frequently came away from conversations in the past feeling that even if I was successful in convincing people that the peer reviewed sources requirement needs to change — I was leaving them without any good ideas for how to make that change. I always gave examples and suggestions of things that I have seen others do that I like.

(Many of these are captured here on the Effective Research Assignments blog).

But they just feel like disconnected specifics. I think that it’s hard for people to see how they might adapt them if their situation differs in any significant way. This time, however, I was able to point to a “thing that people do” that each one illuminates. For example, the research map we use at OSU that I’ve linked to so many times here that I won’t do it again clearly connects to “People do research, original research.” But I was delighted to find that almost every thing I have suggested in the past about teaching peer review connected to at least one of these easily. And I think this made it easier for people to translate those examples to their own practice in their own fields or communities.

So obviously, this is early days with this thinking, but I’m interested to see where it takes me and if it resonates with anyone else.

4/12 – minor, minor edits to fix some annoying typos

What a thoughtful and thought-provoking read, Anne-Marie. Thanks!

This is really, really interesting, especially as I’m leading a team to redevelop our “skills” curriculum – a set of core modules which are primarily about “Doing the Discipline” and run from first year “how to use the VLE” to the final year independent honours project. One theme that has come up a lot is how important it is for us to find ways to acculturate our students – to help them learn quickly how university is different from school, what the expectations and norms are,where to focus the (inevitably limited) time and energy they have for their studies to get the most out of them. Many of our students are first generation to university, most come from lower or lower-middle class backgrounds where degree-requiring “professional, white-collar” work is not the family norm and from the sort of education system where most of the resources are focused on managing the students who need minimal qualifications to be employable, and on helping students get from D (essentially fail) to C (pass) in the key public exams at 16 and 18, rather than on helping Bs understand what they need to do to get As. Helping them learn enough about how this new place works to thrive in it, without requiring them to ape all its mores, matters.

I’m STEMM trained, I don’t have the language often to share these ideas with colleagues (although students taking the courses are taking degrees which can be humanities, social science or science focused, so my ‘audience’ for the skills strand has to be all of the faculty taking the students in later classes) – would you mind if I borrowed those two slides as a starting point?

Of course you can. I’m thrilled to hear it may be useful for you. This is a topic very dear to my heart.

I used versions of this content in some faculty workshops I did last year as well. The slides for those are on my public presentations space on Google drive. Look at the presentations for AMICAL 2015, USF 2015 and UNM 2016 for some slightly different versions (mostly different in aesthetics) :)