Reflections on Reflection. Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Meta

Slides

PDF version of the slidedeck

Bibliography

Zotero folder (books, articles, videos)

Script

Note 1: I used this to create the talk, and to practice and refine it. I didn’t bring it up with me to the podium. I spoke from a cryptic set of speaker notes attached to the slides. So while I think this is an honest reflection of what I said in the talk, there will be places where it doesn’t match exactly how I said it.

Note 2: Most of the slides link directly to an image page on flickr. The rest link to larger versions here.

Note 3: Big thanks to Rachel Bridgewater and Catherine Pellegrino who helped me turn this from 2 hours’ worth of thoughts connected in my head into a talk understandable by other people. Any remaining confusion is my fault alone.

Thank you for that introduction and thank you to the committee for inviting me. I have to admit I’m a little intimidated to be up here. LOEX was the very first national conference I ever attended. That was 2005 and right now, 10 years doesn’t seem like very long ago. So many of the people in this room have had such a major influence on me and on my thinking — I just think the bar at LOEX is set really, really high.

When I was invited to give this talk I was deep down a rabbit hole thinking about reflective practice, emotion and learning. So when the committee suggested that as a topic, I jumped at it.

When I resurfaced from that and I had to actually settle on a title and abstract I started to worry a little bit. I mean, this is a topic that can get pretty autobiographical. It’s personal and idiosyncratic – what’s mindset shifting to me is probably totally obvious to lots of you. But most of all, let’s face it – reflecting on reflection can turn into a mountain of meta that doesn’t really seem like the most productive place to be.

So I worried, and that worry made it into the subtitle. And I wouldn’t say that I have stopped worrying and learned to embrace the meta — but I am working on embracing the discomfort that comes with it. And that’s actually what I am going to talk about here today.

But before I start into this story — let’s talk for a minute about reflective practice.

- How many of you build time for reflection or metathinking (thinking about thinking) into your instruction sessions?

- How many of you would say that you do the same in your practice — build in time for reflection, or thinking about your thinking?

- How many of you would if you had more time?

There’s a lot of research showing that taking the time to reflect on how you think is important to learning. I’m not going to get into that here; I think that metathinking is pretty entrenched in the way we teach in libraries. But if you want a really clear overview, Char Booth’s Reflective Teaching, Effective Learning is a great starting point.

So I’m focusing here on that specific category of reflective thinking that informs our practice as teachers. I’ll take you to where I started on the topic a number of years ago, go through the event that sent me down that rabbit hole over the last year and where that took me.

And I’ll ground all of that in the literature that informed me. There’s a Zotero folder linked from my blog (info-fetishist.org) where you’ll find all of those references.

I started thinking specifically about the role of reflection in teaching practice a little more than 5 years ago in a research project that I did with my colleague Kate Gronemyer.

This project was strongly influenced by the book The Reflective Practitioner, by Donald Schön. Schön is really interested in that “practice” part of the phrase — he wanted to understand how practitioners (as opposed to researchers or experts) make decisions and solve problems both in the moment (which he calls Reflection In Practice) and after the fact (Reflection On Practice).

He assumes that professionals don’t just implement strategies or follow theories developed by experts, but that they also draw on a big body of knowledge built through experience. And he wanted to figure out what good practice knowledge does and how professionals to capture and share it.

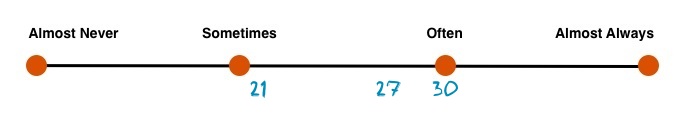

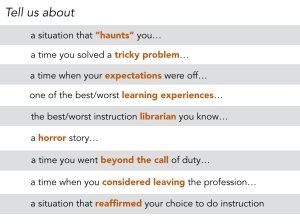

We gathered and analyzed a collection of stories that teaching librarians told about their practice. These were the story prompts. (Well, the actual prompts were longer, we’re good academics, but these are the salient bits) We each coded the stories and then identified themes together. We also took note of the practice environment where the story happened (when we could). All told, we identified about 8 themes and I’m going to dig into two right now.

First up is power.

I should mention here that all of the codes could skew positively or negatively — I could talk about being totally empowered in a situation or about being totally disenfranchised and so long as I specifically invoked the concept of power in the story — that code would apply. When you see that most of these codes came from these story prompts — tell us a horror story, or tell us about a situation that haunts you, you can probably guess that most of these were negative.

And when I tell you that almost all of these were about the one-shot, I’m guessing you can guess what kind of things were coded this way. Some, focused on specific moments.

And others were about a specific event, but mentioned the power relationships in play — like this one, that focuses on faculty. Or there might be a librarian who says, “I’m the instruction coordinator, but I can’t actually compel any of my colleagues to teach.”

The second theme is flexibility, which actually gets at another aspect of the same dynamic. There’s something out of my control, so I have to be flexible. So horror story is still up there, but the second most common prompt was, tell me about a time when your expectations were off. But this one is interesting because the code also showed up a lot in stories where people were talking about extremes or ideals — the best teaching librarian you know, or the worst learning experience ever.

Taken as a whole, the stories connected to this theme gave the strong impression that for instruction librarians there is a lot of basic stuff out of our control. I mean, the teaching environment is uncertain for everyone — there are people in it — but for instruction librarians there are just basic pieces we have to adapt to. I’m guessing that’s not a controversial statement.

Taken together with power, however, we couldn’t help coming away with the idea that despite this, we instruction librarians we take an awful lot of responsibility on ourselves. In fact, the story that included this second quotation was actually pretty extreme — we’re not talking about “dude got behind and his students don’t have the assignment yet.” There was a changed assignment, technology problems controlled by another department and the faculty colleague was really more of an active saboteur. But to this librarian the main takeaway was her failure, in the moment. And that kind of thing came up came up again and again.

So it seemed clear to us that we have some simple, shared, narratives out there about what good library instruction is — and that a lot of us are using our reflective practice to compare ourselves to these smoothed out, idealized models.

And you can see why, right? Because there’s safety in these narratives. If I succeed, I’m comforted by the fact that I knew what to do to succeed. And even if I fail, if I can find the place where I didn’t match up to the narrative — I didn’t use enough active learning, I wasn’t flexible enough — then that promises safety in the future if I just match up.

But at the same time — horror story, situation that haunts you — it was clear that these narratives also generate a lot of stress, anxiety and angst.

So, we needed a different model of reflective practice — which brings us to critical reflection. Here we were informed strongly by Stephen Brookfield’s Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher.

For Brookfield, the goal of reflective thinking is to identify and question the assumptions that lie under the surface of our practice. These assumptions can be causal — about what causes what — so, sitting in a circle makes people feel equal. Or prescriptive — about what good teaching is — for us, one of those would be active learning is best. Or they can be paradigmatic — big, world-view type assumptions – I’ll be talking about those throughout the rest of this talk.

And over all of these, he especially warns us to watch for hegemonic assumptions — assumptions that seem fine, but can cause us to be complicit in our own oppression.

And what does that mean? Well, I would consider “a good librarian will fix any problem related to her students’ learning in the moment” — to be hegemonic. That narrative lets me focus all of my work to fix the problem on me and my own teaching, on developing a big enough bag of tricks to respond to any situation. And I don’t deal with the underlying issues with the course instructor — about the power relationships between us or about the things they are doing that sabotage their students’ learning.

Now, of course this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try and give students a good learning experience — of course I’m not saying that — but in our reflection on practice our analysis should be much, much more complicated than “I failed because I wasn’t flexible enough.”

And he gives us the lenses across the top there — our own experience, information from students, information from peers and information from theory — as tools to ferret out and analyze those assumptions.

So, Brookfield’s approach really really works for me. Identifying problems, and then intellectualizing them — gathering and analyzing data and trying to understand them in a new way — that’s right smack dab in my comfort zone.

Which means that earlier this year I was reading a book called Engaging Imagination – mostly because it was by Brookfield and another education scholar – Alison James. They make the argument for building play, imagination, metaphor and movement into reflective classroom activities.

Now, I read a lot of this kind of stuff, I even seek it out. But I don’t really do any of those things in my own reflection — I stay in my head, in my verbal, analytical place where I intellectualize my problems.

So when I seek these things out, I’m doing it for my students — I’m doing it because I think metathinking is a really important part of the learning process and I know that reflective assignments make a lot of people uncomfortable. So by offering as many modalities as possible, I’m trying to ensure that everyone gets a chance to be comfortable in reflection, at least some of the time.

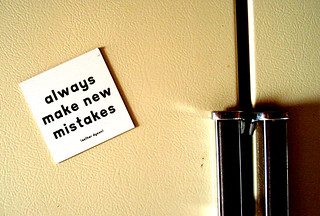

But early on in this book, Brookfield and James said something that hit me like a ton of bricks. They said that’s not why we do this. The reason to build a lot of reflective methods into your class isn’t to make everyone comfortable — the reason is to make everyone uncomfortable, at least some of the time.

Now, when I read this — this discomfort piece — it just grabbed hold of my brain. And I think that was because it made me realize how uncomfortable, even upset, I get when I am asked to veer away from reflective analysis and writing. If you ask me to do it in a workshop — I’ll do it, I might even enjoy it once I start, but when I first hear that we have to create clay models or something my first reaction is to be upset, flustered, defensive, maybe a little angry and internally yelling oh no no no no no no no.

And here’s the thing — I totally should have known better. I should have known this all along. Because as much as I love reflection and do it all the time, I don’t do it for real when I’m told to do it. Workshops, courses, annual self-appraisals – seriously, my memory isn’t perfect — but I can’t remember a time when I’ve done real, meaningful reflection as an assignment.

14 year old Anne-Marie, sitting in her parents’ living room with fourteen pens and a spiral notebook – writing a whole term’s worth of reading journal entries in one night. That’s how I did every journaling assignment I ever did – high school, college, library school — the night before they were due.

See, I’m not saying this worked for me (and it did, I got A plus pluses on reflective writing) because I am so super good at reflection. That is absolutely not what I am saying. It worked for me because I’m super good at reflective writing assignments. It’s not about my writing, or reflecting, it’s that I always know exactly what my teachers want to see. I know the kind of learning they want to see, the process they want to see, how they want it communicated and I deliver it. I’m not reflecting to learn, I’m performing.

And I didn’t even feel bad about it. I still don’t – not really. I mean, I don’t shy away from reflection in my real life. That larger life skill learning happened. I value reflective practice, and I work actively to do it better. But after reading Engaging Imagination there was no way I could avoid realizing that if I’d been pushed out of that verbal, analytical comfort zone more I may have seen things or understood things that I missed.

And that could have been the end of it, but it wasn’t. Seriously, this bugged me for days. I just kept churning on it.

Because there are unwritten narratives in play here too. Embedded in these “show us what you learned” assignments are assumptions about what kind of learning, analysis or process is valued and valid. And those narratives are usually unwritten, and unspoken — that’s one reason why these assignments cause so much angst with so many people. They favor some students more than others, and I was one of those favored few.

It made me see that a lot — maybe even most — of my own reflective thinking has been spent on trying to help my students join me in my comfort zone, without questioning the narratives and assumptions underneath.

And this made me deeply, profoundly, uncomfortable — because it’s a really incomplete way of looking at learning.

And it’s a superficial version of reflective practice. I’m taking my students’ experience and filtering it through my lens — which is obviously going to distort it. It inherently makes me focus on gaps, places where they don’t match up. And on figuring out ways to make them match my assumptions about learning. This puts all of the burden of significant change on my students. After all, I’m reflecting on their experience. I’m not really reflecting on my own.

Which brought me back to my initial, emotional and defensive reaction to those assignments — and I dove head first into the rabbit hole that is emotion and learning. As you do.

One of the deeply, deeply entrenched narratives in western culture is the mind/body (or thinking/feeling) binary, or the idea that logic, reason and higher order thinking are separate from — and even disrupted by — emotion, passion or feeling. Knowledge construction in our culture is a sober, analytical process based on evidence and data — not feeling or experience.

Last spring, I was at the American Educational Research Association’s conference in Philadelphia and at that conference AERA presented their Early Career Award to an “affective neuroscientist and human development psychologist” named Mary Helen Immordino-Yang. And her work — which connects social emotion, cognition and culture — totally captured my imagination. So when I started exploring this topic in earnest, I came back across her work and entered this kind of fugue state where I read everything she’s ever written.

So basically, into the eighties the research about the brain and learning reflected the binary I just mentioned. The idea was fairly entrenched that reason, logic and thinking and emotion were separate, controlled by different parts of the brain. But there were anomalies. And they disrupted this prevailing narrative, as anomalies often do.

These anomalies were patients whose cognitive functions seemed to be intact, but who showed gaps in their decision making. They weren’t able to consider the consequences of their actions. They were insensitive to the impact of their choices on others. Basically, they weren’t able to learn from their mistakes, so they would make the same terrible choices over and over.

But here’s the weird thing — they could TALK about that stuff just fine. They could explain the risks involved in their business decisions. They could describe social norms. Cognitively, they seemed to have what they needed to make good choices, but then they didn’t. So it seemed likely that the affective domain was in play.

So when researchers studied what was going on in these brains they concluded that when we experience things, we “tag” them with information about how those choices or decisions worked out for us. And this information is stored with our emotional knowledge. Without the ability to access the parts of the brain that manage that emotional information — how we felt about those choices — we can’t use it to make good decisions moving forward. So emotion doesn’t get in the way of thinking – emotion is an essential part of higher-level thinking.

In fact, one of the most interesting hypotheses Immordino-Yang suggests for higher education is that it is this emotional rudder (her metaphor) — or the ability to draw on the emotional knowledge associated with our past experiences — that helps us transfer knowledge from one experience to another. Particularly relevant to instruction librarians — we need our students to be able to transfer what they learn from us moving forward.

These new lines of inquiry mean re-thinking what we mean by survival. One of the narratives in the thinking/feeling binary is that strong emotion kicks in when we’re under threat and need to feel safe. But that narrative mostly focuses on physical harm – the idea that when we see the car heading for is it triggers a basic, emotional response (Immordino-Yang says “in the alligator brain”) that protects us.

But as our world got more complex, so did our understanding of survival. Survival now goes beyond our physical safety as an individual and includes other people and our social relationships. Those emotional tags we put on our experiences aren’t about us in a vacuum, they’re all about how our choices affected other people and how that bounced back on us.

So protecting ourselves against threats to our status and identity is every bit as important as protecting ourselves from physical harm. Emotion is still basic decision making — I want, I feel — but more advanced cognition doesn’t replace it. Instead, higher level reasoning lets us pick and choose and customize our responses in more sophisticated ways.

So, what are my takeaways from this?

- That strong emotional reaction I have to certain kinds of learning experiences should be telling me something — emotion is part of why we create simple, smoothed over narratives in the first place and why we don’t poke at them — we’re protecting our core, our identity, our place in the world

- Emotion is necessary to thinking and in particular, it’s an autobiographical emotion. Connecting to our experiences and our feelings around them is necessary to evaluation, analysis – those higher level processes.

- That autobiographical emotion isn’t fully internal — it’s shaped by our interactions with other people and with culture. We can’t really critique our assumptions and narratives without understanding those influences.

Now, there are many people — some informed by feminist theory, queer theory, critical race theory and others working from more traditional perspectives — who have challenged the thinking/ feeling binary — making the case for bringing the whole student, not just the cognitive student, into the learning process. And this is a body of work that had been building for decades. So some of this feels a bit like science is catching up to theory and experience.

And where I am going now with this is pretty strongly influenced by a group of scholars like Megan Boler, Laura Rendón and Kevin Kumashiro, who are grappling with the question of how to create safe and meaningful classroom experiences when you are specifically asking students to question and dismantle deeply held beliefs. These scholars have a commitment to anti-oppressive practice, in many cases because they’re teaching courses on topics – about race, gender, sexuality – that inherently ask students to examine some of their core ideas about identity and self.

Now, it might seem like instruction librarians are doing something different — asking students to “find and cite 3 peer reviewed sources on reintroducing wolves into Yellowstone” seems pretty different from asking them to dissect their privilege. But a lot of this work resonates strongly with me as an instruction librarian. In many ways, I think asking students to question and dismantle deeply held beliefs — or at least be willing to do so — is exactly what we do.

We’re asking them to engage in open-minded inquiry. And at the very least, this means they have to consider the possibility that they might change their minds about something that they care about. And if they care about it because it says something about where they’re from, or their family history, or what they want to do, or things they believe in — that’s threatening. And this applies too to the basic things we do — we might be asking them to rely on sources and discourses they’ve been taught since birth to be skeptical about. Or sometimes we ask them to put aside sources and texts they’ve always believed are valuable sources of wisdom about the world.

And even if we don’t do so overtly, what we’re asking them to do might also require them to dismiss habits of learning and research that have probably served them very well in the past, through many years of experience, and to internalize new ways of thinking about knowledge, evidence and information.

All of these things reach right down into the identities we construct for ourselves — what we believe is right, what we believe is wrong, where we find wisdom, what we value as thinkers and learners — these are all essential parts of who we know ourselves to be.

I think it’s fair to say that to be information literate is to be okay with the idea that what we know in our core to be true could change tomorrow — and that’s terrifying. And so I believe that it’s only fair that we hold ourselves to this same standard. Starting with — or at least for the purposes of this talk focusing on — our reflective practice.

Historically, we’ve treated feelings in education (and honestly, in other arenas too) as something to control or suppress – push them down so that thinking can happen. And we’ve also used this as a way to control or suppress people who have historically been considered more emotional or less rational.

And I think that there’s an element of this controlling, suppressing and managing narrative in our thinking about reflective practice as well. As much as I love Brookfield, I can’t deny that the thinking/feeling binary undergirds much of the argument in this book. There’s a strong through-line that essentially frames the process of critical reflection as a process of intellectualizing the emotional and cognitive challenges of teaching. I mean, he comes right out and says it — if we don’t critically reflect “we are powerless to control the ebbs and flows of our emotions.”

And I’ll admit that this is also my comfort zone. This is how my brain works. In fact, I’m sure this is what I was serving up in all of those reflective writing assignments — watch me intellectualize my emotions and learn and grow. And here’s the thing — it’s not like this isn’t super useful in teaching. And it’s a big part of what makes up effective reflective practice.

This is where things get tricky for me. There is a lot I like and want to preserve about my comfort zone, about reflective practice and more broadly. I think there is value the type of inquiry embedded in “college level research.” I think there’s fun, creativity and enjoyment to be had in these intellectual exercises and practices. I like stretching those muscles and I think they’re muscles that need to be worked and skills that need to be practiced. I think when people can do this they’re more powerful and able to make things happen.

But when we’ve tried to divide thinking and feeling, that doesn’t just mean pushing emotions aside — it also means elevating lots of things that are traditionally associated with rational thought or inquiry. We reject the importance of experience, lived experience, in favor of science and “rigorous evidence.” It’s an either/or thing.

And if this isn’t how thinking works — if this isn’t how humans evaluate and consider and decide and choose — we need to be able to connect the pieces of this binary together and find new spaces somewhere in the middle.

Megan Boler wrote a wide-ranging and provocative book called Feeling Power — about the power of emotion and also about the ways that feelings have been used to control and dominate within education. She closes by outlining ideas for a pedagogy of discomfort. I’m not going to do this book justice here — and I’m doing even less justice to the huge body of scholarship that inspired her — because I’m going to zoom in on just one of her points — the need to resist simple binaries, the things we construct to make sense of a complex world.

A lot of these binaries are in play in our classrooms, not just thinking/feeling: novice/expert — scholarly/popular — individual/collective — theory/practice — objective/subjective — I’m sure you all are thinking of more. When you start to scratch at some of the idealized narratives underneath our practice you’ll find them. We create and hang on to these binaries to make sense of a complicated world. But when we internalize these simple structures, it gets harder to deal with the implications of our critical reflection.

Here’s an example. A big binary that frames a lot of our thinking is about people — good/bad – deserving/undeserving – guilty/innocent. We’ve all probably internalized it to some level, even if we fight it.

One of the most powerful things we want is learning that reaffirms our self-image. If we’ve internalized that binary good/bad/innocent/guilty — then when we think we might be contributing to something that hurts our students, we feel guilty. We feel all of the feelings related to that. And our self-image can’t handle the idea that we’re guilty so we resist. We will ourselves not to see the issue — Boler calls this inscribed habits of emotional inattention — or we use our reflective practice to rationalize the original critique away.

Because here’s the thing — metathinking, reflective thinking, even critical reflection — these methods or practices can be used to justify and entrench just as easily as they can be used to illuminate and dismantle. And honestly, I think the more adept you are at the motions of reflection the easier it is to use it to justify whatever you want it to – especially if you’re not aware that you are doing it.

Committing to finding spaces between these binaries lets us deal with this complexity — we’re not good or bad — we’re in the middle, it’s not all about us and which side we’re on, and we can deal with all of the complex factors that go into the situation.

But this isn’t easy. It requires us to accept a scary level of uncertainty. This is a shifting landscape – we’re between the binaries here today and we keep thinking and working — we’re somewhere else tomorrow. And really, it shows that some of the identities we construct are actually pretty fragile themselves.

And maybe librarians are the best people to navigate this uncertainty with our students. Because we already straddle binaries — between theory and practice, scholar and practitioner, specialist and generalist, novice and expert — you can probably think of more. We’re unique on our campuses; we’re already in the grey areas.

I have a colleague in Oregon, Sara Seely from Portland Community College, who tells her classes — I know about all of your assignments and what all of your teachers want and I’m not grading you — I’m totally on your side.

I just love that. I love it because we so frequently frame this as a barrier — we don’t have access to the carrots and sticks built into the system — but it can be liberating.

Most of us do not have majors, minors or degree programs to manage. Most of us can’t compel attendance or attention. It’s true. But if we’re not benefiting from those systems, then we’re not bound by them either.

We teach, and we want students to do well in our classes but the end game for us isn’t their performance on the end of session quiz. Traditional metrics like grades don’t even capture much of the teaching work we do.

We teach, and we want students to learn, but we really want them to take what they learn and use it later — so we can focus on what they need to integrate and transfer that knowledge.

We teach, but we don’t have to weed out students or protect the rigor of our programs. We can make the unwritten rules, values and rewards transparent to all of our students, even if they don’t come in with that knowledge.

We teach, but we’re not going to be judged at the end by how well our students master a body of content – we can afford to complicate the picture for them and follow where they explore.

And the thing that’s powerful about sitting between binaries comes from rejecting the idea that we need to make either/ or choices – or align ourselves with one set of entrenched values. From our position, we can help students learn a new culture and make its norms and assumptions visible and transparent while also doing what we can to dismantle structures that exclude, hurt and discriminate.

But that can be scary. And uncomfortable. There’s a timidity sometimes that pops up in our profession that says — “if I draw too much attention by challenging the norms they’ll take away what I DO have in the academy.” I’d like to see us fight this more actively – to say we are different and this is what we do and we’re the only ones who do it and that’s the value we bring to campus — and commit to building that case.

Because we can’t do all of this if we align ourselves with simple narratives — whether we define them for ourselves or maybe especially if they’re defined for us. No matter how safe they make us feel.

And so, in the end, we need to embrace the discomfort because if we focus on choosing the side that will make us feel safe I don’t think we really are.

So. as it turns out, ending a talk when you feel like you’re still in the middle of the topic is harder than you’d think. I’m going to be exploring the gray areas on this one for a while. I hope we all can keep talking about it.

Questions?